Joke of the Day! How the Manager Tackled the Potatoes

The relentless hum of the corporate machine defines a specific type of existence, one where the soul is often traded for a title and a high-functioning nervous system. This was the life of Arthur Vance, a senior vice president at a global logistics firm. Arthur lived by the calendar, his pulse synchronized to the erratic fluctuations of the stock market and the ping of incoming high-priority emails. He viewed sleep as a strategic weakness and caffeine as his primary fuel source. However, the human body has a way of vetoing a lifestyle that the mind insists is sustainable. One Tuesday morning, midway through a PowerPoint presentation on quarterly optimization, Arthur’s heart gave out.

The heart attack was a brutal wake-up call. Following a successful surgery, his doctor delivered a non-negotiable ultimatum: Arthur was to vacate his corner office and spend a month in total isolation from the digital world. The prescription was simple yet terrifying for a man of his temperament—three weeks of absolute quiet on a remote family farm. Arthur initially fought the suggestion with the fervor of a man defending a merger, but his physical frailty eventually forced him into a reluctant surrender. He packed a bag, left his smartphone in a locked drawer, and drove into the rolling hills of the countryside.

Upon his arrival, the silence was physical. It pressed against his eardrums, uncomfortable and alien. For the first forty-eight hours, Arthur paced the porch of the farmhouse like a caged predator. He missed the adrenaline of the boardroom and the constant validation of being the man with all the answers. By the third day, the tranquility had become a form of psychological torture. He approached the farmer, a weathered man named Silas who seemed as rooted in the earth as the ancient oaks surrounding them, and demanded work. He needed a project, a metric to hit, a mess to manage.

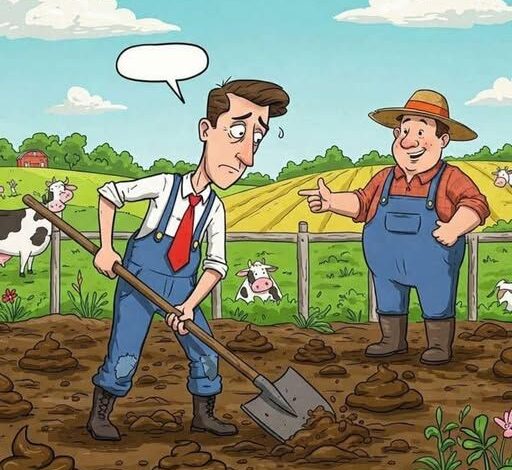

Silas, observing the city man’s frantic energy with a mix of amusement and skepticism, pointed toward the barn. It was a cavernous, neglected structure filled with months of accumulated cow manure. It was backbreaking, filthy work that most city dwellers would recoil from. To Silas’s shock, Arthur attacked the task with a ferocity usually reserved for hostile takeovers. By sunset, the barn floor was immaculate. When Silas expressed his amazement at the speed of the work, Arthur merely wiped the sweat from his brow and offered a grim smile. He told the farmer that he had spent twenty years cleaning up much larger messes at the office; at least the manure in the barn didn’t pretend to be something else.

The next day, Silas presented a grimmer challenge. There were five hundred chickens that needed to be processed for the local market. It was a visceral, bloody task that required precision and a lack of sentimentality. Again, Arthur didn’t flinch. He worked with a cold, mechanical efficiency, and by the time the evening shadows lengthened, every bird was ready for transport. He explained to a stunned Silas that his entire career had been built on making “cuts”—he had terminated departments, ended long-standing contracts, and severed professional ties without blinking. Doing it literally, he remarked, was surprisingly less stressful than doing it metaphorically.

On the third day, Silas decided to give the high-powered executive a reprieve. He led Arthur to a shaded area behind the granary where several massive burlap sacks of potatoes sat on a wooden table. Silas placed two empty crates in front of Arthur. He explained that the task was simple: sort the potatoes. Large, blemish-free potatoes went into the left crate; small or misshapen ones went into the right crate. Silas left him to what he assumed was the easiest job on the farm.

When Silas returned at sunset, he found Arthur exactly where he had left him. The burlap sacks were still full, and the two crates were completely empty. Arthur was slumped over the table, his head in his hands, looking more exhausted than he had after shoveling the barn or processing the poultry. He looked up at Silas with a face etched in genuine agony. He confessed that he couldn’t do it. Silas was baffled, pointing out that Arthur had handled chaos, filth, and blood with ease.

Arthur’s response was a revelation of his own professional pathology. He admitted that in the corporate world, he hadn’t actually made a real decision in years. He realized that he had spent his life hiding behind committees, memos, and data sets. Every choice was deferred to a meeting or buried in a consensus-building exercise so that no single person ever bore the weight of the outcome. In the office, a “bad decision” could be recontextualized or blamed on market volatility. But here, standing before a single potato, there was no committee. He had to decide—large or small—and he had to own it. Every potato felt like a personal performance review that he was failing.

Silas let out a long, slow whistle, realizing that the manager had become a prisoner of his own bureaucracy. The man could handle a crisis, but he was paralyzed by the mundane. That night, Arthur didn’t sleep. He sat in the dark, reflecting on how he had outsourced his own agency to a system designed to avoid accountability. He realized that his “success” was built on a foundation of avoidance.

The next morning, Arthur returned to the table. He picked up a potato, looked at it for a second, and dropped it into the left crate. Then another into the right. He moved slowly at first, but with each toss, he felt a strange sense of liberation. He told Silas that he finally understood: not every decision required a strategic roadmap. Some things were just large, and some were just small, and the world didn’t end if you picked wrong. By the end of the week, Arthur was sorting potatoes with a rhythmic, peaceful confidence. He even took an interest in the culinary side of his labor, learning to prepare a simple dish of roasted potatoes seasoned with olive oil, rosemary, and sea salt—a stark contrast to the complex, overpriced meals he usually ate in the city.

When Arthur’s month was up, he returned to the glass-and-steel towers of the city. He walked into his office a transformed man. He was calmer, more decisive, and possessed a newfound kindness that confused his subordinates. He dismantled the culture of endless meetings and began empowering his team to make their own choices without fear. When his chief of staff asked what had happened during his sabbatical—what groundbreaking management philosophy he had discovered—Arthur simply laughed. He told them that an MBA teaches you how to manage data, but a potato teaches you how to live. He had learned that the courage to make a simple choice is the ultimate form of power, and that sometimes, the best way to lead is to simply get your hands dirty and decide.